Congress today voted to approve a measure which would extend unemployment benefits to those whose benefits ran out at the six-month mark. The vote was conducted after the swearing in of Senator Carte Goodwin, who cast a vote which broke a "Republican Filibuster" and sent the bill on its merry way.

Those of you who read a previous blog post will know the distaste I have for the manner in which Congress conducts itself, and it is with the new information provided by this most recent abuse of power that allows me to put a finger on what, exactly, disturbs me.

Think back to, say, elementary school. You and ten other students get together on the playground and try to decide what you want to play.

"Hide and Seek!" you shout immediately.

"Red Rover!" another student shouts almost as quickly.

Debate ensues as to which option is more appealing. Being young, the idea of dividing into two groups never occurs to you, or if it did, the idea of a game consisting of only 5 people sounds like no fun. Finally, one student says those fateful words.

"OK, let's vote on it."

The votes come down: five for Hide and Seek, six for Red Rover. Your suggestion was defeated and the group will play Red Rover. This is the nature of the democratic process: A group of people resort to the will of the majority to decide an issue and - and this is truly the most important part of the process - these people agree to be bound by the results of the vote, whether they like the result or not.

A Republic, such as what exists in America, is an interesting twist on Democracy. As a straight Democracy becomes increasingly cumbersome the more people are involved, the people vote democratically on certain, but not all, issues. For the remainder - often, the bulk - of the issues, they select representatives (democratically, of course) who take on the daily business of government and make decisions amongst themselves on behalf of their constituents via the democratic process.

In short, a Republic is a system of government whereby the people engage vicariously in pure Democracy.

Let's return to the playground. In an ideal world populated by honest, mature, and just people, you would accept the outcome of the vote and get on with the game. But what if you refused to accept the outcome, and not only that, but you got your fellow students to vote again and again, until circumstances changed - you bring in other students to vote your way, or players who voted against you leave, or you just bully people into changing their votes - such that you finally got your way? Would that be democracy, or would that be something else entirely?

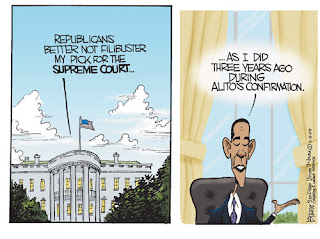

As it so happens, this latter behavior is the manner in which Congress conducts itself with disgusting regularity. It seems that (through abuses of the rules which govern procedure, which I will discuss topically later in this essay) the Pass/Fail vote which is the hallmark of a real democracy has been usurped by a Pass/Filibuster system. The key difference between the two is that after a vote is taken in a true democracy, the issue is settled. In the latter system, a motion only fails to pass for now.

If a Republic is a government in which those selected to attend to the business of the government conduct themselves democratically, then what else can you call the refusal to be bound by democratically achieved results than a perversion and a failure?

As I said before, the most important detail of this system is not so much the process itself, but the understanding that the participants agree to be bound by the process. In most representative governments, the process is codified well beyond "we vote on stuff". Several such systems of rules exist and are commonly referred to as "Parliamentary Procedure" and they exist in order to organize and expedite efficient discussion and voting. Rules are crafted to determine who may speak, what may be discussed at a given time, what gets voted on when, and numerous other instances which require consistent procedure in order for discussion and the process to be deemed fair.

It is also common within democratically derived systems to set certain rules upon the voting itself. For instance: it is generally understood, but in some cases need be stated explicitly, that a single person may cast a single vote. In a case where a single person may cast multiple votes, information such as how many votes a person may cast and how they may cast them must be delineated. Some rules apply to determining an outcome - certain issues, such as amending the Constitution, are deemed too important to be left to the whims of a simple majority and must be approved by "supermajorities" of two-thirds and sometimes three-quarters of the vote.

In these systems a motion may be made, discussed, and amended; other motions may be substituted; and any or all of these may be tabled, denied consideration, or voted upon. What they have in common is that, once a motion is voted upon, the issue is settled, yea or nay, good or ill. The question cannot be raised again unless significant new developments occur, a pre-determined length of time passes (usually requiring a new term of office or a new session to begin), or the motion changes substantially.

No parliamentary authority recognizes the addition of pork as a "substantial change" unless the subject being discussed is Lunch.

One of the principal difficulties of these parliamentary systems (principal, as anyone who has spent any time in a board room or convention can surely describe the many subtle and nuanced failings of whichever system they experienced) is that the more rules are in place, the greater the opportunity for abuse. These rules are in place to move discussion along, to keep it organized, and to assist in keeping track of what is being voted upon and what happens when it passes or fails. Societies who implement parliamentary procedure are often fond of saying the rules are "intended as a loose-fitting blazer, not as a straitjacket." And while this sentiment is certainly true of the authors' intentions, the "spirit of the law" is often usurped by the "letter of the law" and we find ourselves watching Congress.

The current congressional paradigm of Pass or Filibuster means that there is not a single hare-brained piece of malevolence that can be moved and seconded in those halls that will ever disappear. If it fails to pass on a vote, rather than being eliminated until a better (or at least different) idea comes along, it sits dormant, a victim of "filibustering" until somebody retires, dies, or forgets to show up to a session and the vote can finally swing the other way. Any measure with a chance of passing greater than zero will, given enough time under a "filibuster", be passed and inflicted upon America.

The recent passing of the unemployment measure may have been done technically within the bounds of the parliamentary authority but the manner in which this task was completed was not only contrary to spirit of democracy and the parliamentary authority, but shows open contempt for the fair, open, and enlightened intentions of the processes.

For those of you who doubt me, there is a footnote worthy piece of information: the next step in the process of implementing the measure which inspired todays blog is for the Senate to choose whether to incur more national debt, or to cut funding from other government programs in order to finance their decision.

How fortunate for us.

0 comments:

Post a Comment